I never got a satisfactory explanation from my father as to why he uprooted us from San Jose, in the middle of my Fourth-grade school year and transplanted us on to a strawberry farm in Watsonville.

“It was 1956 and my Tia Alicia, Tio Antonio and their seven daughters were farm workers living in a three-bedroom, one bathroom shack on a huge strawberry farm close to Highway 1, the Pacific Ocean, in the agricultural community of Watsonville.”

Dad and my Tio Antonio, constructed a one room addition onto my Tio’s existing shack. Today, it would be called an “efficiency apartment.” It had a tiny kitchen, table, chairs, a master bed, a crib for my baby brother, a sofa bed for me and my dog, Mickey, and a TV. We shared the bathroom with my Tia, Tio and primas.

School nights, we lined up like soldiers outside the bathroom and we were allowed ten minutes to shower for the next day of school. Depending on your position in the line, determined whether you took a hot, warm, or cold shower.

Dad never told us why we moved there. We didn’t move there to become farm workers. I certainly didn’t. I worked one brief morning on my knees picking strawberries and that was enough for me. The work was deceptively, brutally hard. Besides, this was 1956 and the height of the Bracero Program. There were dozens of them working alongside my Tia, Tio and Primas in the fields.

I became best friends with the son of the Japanese fellow who was the foreman on the strawberry farm. His name was Henry Yoneyama. Henry and I spent long weekends on hunting excursions with our BB guns and trusty dogs at our sides.

We always packed little Leslie saltshakers in our pockets. The strawberry farm owner had a gigantic vegetable garden and Henry, and I would help ourselves to his delicious vine-ripened tomatoes and sweet carrots and season them with our little saltshakers.

We made friends with one of the bracero boys, Lucas. Lucas was blond with green eyes and did not speak a word of English. He was also a deadly marksman with a slingshot, and he made slingshots for me and Henry. Oftentimes, Henry and I would eat dinner with Lucas at the bracero dining hall located up on a hill. The meal usually consisted of beans, arroz con pollo, corn tortillas, pico de gallo and salsa. It was a glorious, goddam gourmet meal.

Sometimes, in the evenings, a couple of braceros would strap on a pair of boxing gloves and put on boxing matches. On other nights, they would play guitars and sing Mexican songs. Henry and I would sit around with them and take it all in with wide-eyed awe, and wonder. It was an idyllic, dream-like existence for a ten-year old Mexican American kid from the city.

But just as suddenly as it began, it came to an end. Without any explanation, my father moved us back to San Jose in the middle of my Fifth-Grade school year. During subsequent summers, I would occasionally go spend a week or two with my cousins, Tia Alicia, Tio Antonio and Henry Yoneyama on the strawberry farm in Watsonville. Lucas had returned to Mexico. I never saw him again.

My father died in 2016 at the age of 94. Up until the day of his death, he never explained to me why we moved to Watsonville or why we came back to San Jose. But now, when I recall that magical time of my youth, I have come to accept that no explanation was ever really necessary.

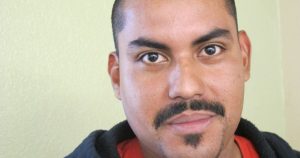

Storyteller Roberto Leal is a free-lance writer, born and raised in the Santa Clara Valley (of California). Both sides of his family are originally from the Rio Grande Valley. He now lives in San Antonio, Texas.