© 1978 Yolanda Lopez

© 1978 Yolanda Lopez

My job as an artist is to create an environment of visual literacy, because if we don’t have visual literacy then we are going to be really helpless—stuck. I’m very much interested in popular culture because I really think that corporate driven pop culture, advertising, is the culture of America. It is perceived as culture because that’s how we get our values.

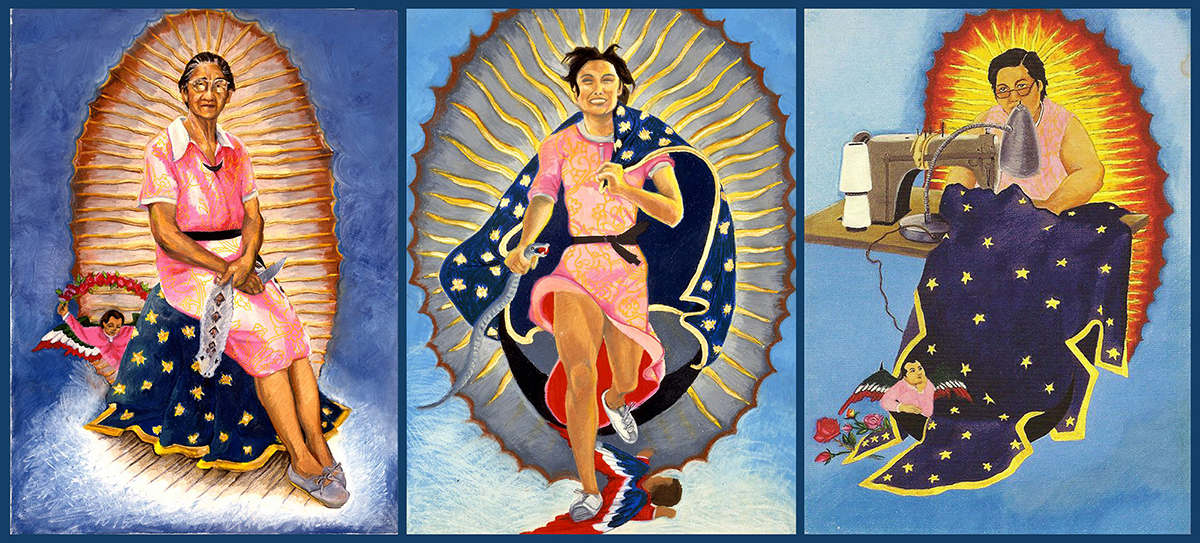

I did The Guadalupes triptych for my presentation for my Master of Fine Arts. In the 1970s, the Second Wave of Feminism exploded while I was in graduate school. It was all East Coast oriented, pretty much upper-middle-class women, without inclusion of women of color or working-class women at all. I also discovered John Berger’s Ways of Seeing*, which was really revelatory. All of this was swirling around and there was a book on body language, how we look at and how we represent ourselves. I honed in on our Chicano Movement to see how we portrayed ourselves and discovered the Virgin of Guadalupe.

I had been baptized, believe it or not, in Guadalupe Church in San Diego. Just outside of Logan Heights. I actually went to catechism. My mother put us in a daycare school run by Catholic nuns, who asked, “Ms. Lopez, you want your daughters to be raised Catholic?” My mother saw the sliding scale and convenient hours and said, “Yes.” Like a lot of children, I was a True Believer for a while. In my teens, teens question everything, nothing is sacred and all that sort of drifted away. My family never went to Mass. We didn’t belong to a Church. We didn’t have any little Christian icons, no Buddha’s, no guys on the cross. None of that was in my house. Even though I was tutored in Christianity I knew very well that I was not a Christian. Nobody mentioned God at all but there was a strong essence within my family—ethics. There was an ethical underpinning to all that we did. My grandmother supported the farmworkers.

Looking at images of women, I thought, let’s see what we’re doing in the Chicano Movement. Since I didn’t have what you might call any emotional strings to the Virgin of Guadalupe, I saw what she meant within the iconography of Mexican-American Christianity. When I show my Guadalupes, I also show the original Virgin of Guadalupe image. She has this long gown that goes beyond her feet. It’s gathered at the bottom and you don’t get a sense of her body beneath it. She wears a pink gown with her belt up to her bodice. She couldn’t walk wearing this gown. But she also has the robe of the nighttime stars and she stands on the crescent moon.

Looking at images of women, I thought, let’s see what we’re doing in the Chicano Movement. Since I didn’t have what you might call any emotional strings to the Virgin of Guadalupe, I saw what she meant within the iconography of Mexican-American Christianity. When I show my Guadalupes, I also show the original Virgin of Guadalupe image. She has this long gown that goes beyond her feet. It’s gathered at the bottom and you don’t get a sense of her body beneath it. She wears a pink gown with her belt up to her bodice. She couldn’t walk wearing this gown. But she also has the robe of the nighttime stars and she stands on the crescent moon.

Then there is the angel at the bottom. He looks like a middle-aged Spaniard. What is he doing? People presume he’s holding her up. He is not holding her up. He’s got one hand on her gown and the other hand on her robe. He’s holding her down! People have lived with the image but have not looked at it.

In doing the triptych I wanted to honor working-class women. The first one was my mother working at an industrial sewing machine, creating her own robe of stars. She doesn’t have to wait around for somebody to confer this robe on her. She’s a workingwoman creating her own.

The other woman that I did was my grandmother, who was about 82-years old, sitting on a stool with her cloak of stars. She’s wearing a pink dress with her usual brooch that’s a crescent moon. She has the rays of the sun behind her.

The third portrait in The Guadalupes triptych was me at the time. I had started running and it freed me up in so many ways. I kicked up her dress so that you could see her legs, knees and all, that there was functionality, a body inside that dress, and that she moves.

What strikes people about this painting is the Virgin of Guadalupe is enthusiastic. She loves her freedom, being herself, jumping off the crescent moon. Unfortunately, there’s that little cherub. He has had to let go of the cloak and let go of her dress. She’s not necessarily stepping on him, but she is certainly jumping over him.

Customarily, women identify with the Virgin of Guadalupe’s pain, the pain of seeing her child die. Whereas men identify with the Virgin of Guadalupe’s compassion, her iconic and all-embracing forgiveness of human behavior.

As Chicanos we don’t portray ourselves, especially women, in a variety of ages, styles and races. There is an attempt at creating heroic women. Which is good, but what do we do? Wonder Woman? Feminism gave me a visual and verbal language with which to work. Justice and Freedom! We haven’t yet exercised our visual creativity in how we portray heroines.

The Guadalupes were my way of experimenting with other ways of looking at women. The whole series is an homage to working-class women, who have had to figure things out the hard way—for themselves.

*John Berger’s Ways of Seeing was published in 1972 as an adaptation of his BBC-TV series of the same name. Both works critique traditional cultural aesthetics and make the case that art reveals the social and political systems in which it was made. Ways of Seeing has had a powerful impact on cultural studies, particularly in introducing the concept of the male gaze vis-à-vis the representation of the female form in art.

About the Artist

Yolanda M. López is a San Francisco–based conceptual artist, educator, and scholar. Born in San Diego, California in 1942, she was raised by her mother and her mother’s parents in the Logan Heights neighborhood. After high school she moved to the Bay Area and in 1968 participated in the San Francisco State University Third World Strike. Since that point she has viewed her work as an artist as a tool for political and social change and sees herself as an artistic provocateur. Yolanda is best known for her groundbreaking Virgin of Guadalupe series, an investigation of the Virgin of Guadalupe as an influential female icon. Classically trained as a painter, her work has expanded into installation, video, and slide presentations. López has taught studio classes and has lectured on Chicano art at the University of California at Berkeley, Stanford University, Mills College, the University of California at San Diego, and the California College of Art.

Learn more about this artist

As a born and raised Mexican catholic I find this very disrespectful, it sounds like they’re bashing and lowering down the importance of our lady of Guadalupe. This whole concept is twisted into the authors convenience and not at all taking consideration of the representation of the Virgin Mary nor of feminism. It does not sit right with me at all and I’m sure the majority of the community Chicano and Mexican community would agree along with me if this article were to be more popular.

A genius gone too soon

I love Yolanda Lopez’ artwork centering on the Guadalupes in action. I’ve always connected with the running Guadalupe. When I initially saw Lopez’s artwork of the Guadalupe in action, I loved her innovation, bravery, and courage in portraying the Guadalupe in this way, reflecting day-to-day life.

Gracias for focusing on the amazing artist Yolanda Lopez!!!

Adriana Ayala